The spirit/muse/guides wouldn’t let me rest. It was the night between the first and second days of a collaborative retreat with some academic colleagues. My thoughts kept winding around the topic of the retreat: restorying our past experiences of human struggle in order to conceive and claim personal and communal agency for hope. (My capsulation of the topic anyway.) It was an interreligious effort with a lean in the direction of Christianity.

In the context of some amazing discussions, someone mentioned the cross as an essential element of the storytelling project we were working on. In the midst of all the Christian storytelling examples and logistical discussions, mention of the cross felt like a beam of light. For many the cross is the center of the gospel, which for the most part is how many of us identify as Christians.

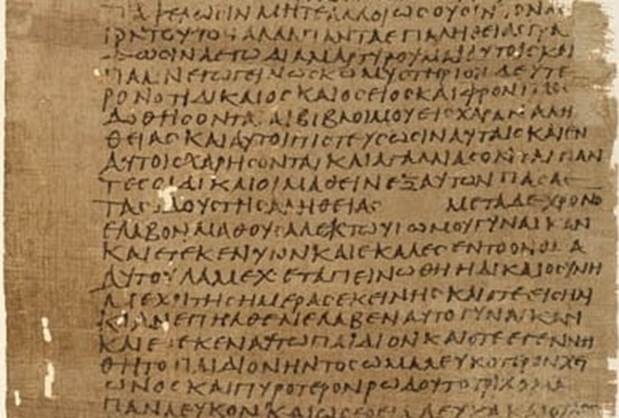

My teaching for the last almost 10 years has focused on the work of scholars like Edward Said, Homi Baba, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Naim Ateek, Munther Isaac, Leela Ghandi, James Scott, Richard Horsley, and many others. Horsley’s prolific work on Empire criticism and the New Testament has been of particular interest to me for shaping my pedagogy in the classroom in urban Detroit. In short, it’s a way of reading the New Testament that brings out the story of human trauma of economic oppression and exploitation in first-century Roman Judea and the struggle to overcome this trauma as that story is embedded in the New Testament. In some of his works, Horsley struggles to make sense of the cross and views it as a sort of mistake of history that just happened to Jesus. I’ll come back to the cross.

Anyway, I couldn’t sleep; I was taken into a sort of Socratic self-interrogation of what the educational components of our storytelling project might look like, trying to distill the approach into what we all share together in our individual and collective human experiences. What do we all share in common, both inside and outside the church, just as human beings? It’s not social or economic status. It’s not family. It’s not education. It’s not even faith. (Insert here all the other points of human connection that can sometimes be characterized as common to our human condition.)

I can only think of one thing that binds us all together. Trauma. We all have it in some shape of form, to varying degrees, but we all share it. Conflict, struggle, loss, grief and grieving. Here the cross becomes the point of reference in the Christian story. My formal theological education happened almost 40 years ago. I learned then what I think was an important piece of my pastoral formation and approach, something Philip Melanchthon wrote in the 1530s. I’m paraphrasing but it goes something like this … human suffering is given its fullest meaning when viewed in light of the suffering and death of Christ on the cross. I struggled to understand what this meant. I applied it to other people’s lives for decades as a parish pastor. It really only became real to me personally when I experienced the unexpected death of a close family member almost five years ago. To connect all of this to our storytelling project I want to share a quote of Franz Kafka’s with you …

“I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us…. we need books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves.”

I don’t know the precise context of Kafka’s words; they were written in a letter to one of his editors, who was probably urging Kafka not to be so morose, so scotic, in his storytelling. My way of applying this to our project is to substitute “stories” for “books” in Kafka’s appeal to his editor … “we ought to read only the kind of [stories] that wound or stab us … we need [stories] that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves.” I had to repeat those words because they are so impactful for me in relation to my own traumatic loss.

The cross becomes God’s way of showing us our own humanity, to reflect our trauma back at us. To make us so appalled by the suffering of Jesus that we would never dare impose suffering of any kind intentionally in any way on another human being. It’s transformative. Paul calls it forgiveness of sins, but that’s an abstraction that I think in our American Protestant context has caused a dearth of sacred community and an over emphasis on individual “faith” and “salvation,” to the impoverishment of empathy, compassion, and acts of justice for our neighbor. The literary gospels in their presentation of the crucifixion narratives never mention “forgiveness of sins” in relation to the crucifixion. In this sense, the ending of Mark’s gospel is closer to Kafka than the others. In Mark’s gospel the women come to the tomb with the expectation of finality and decay, a monstrous space designed specifically for desiccation and absence of hope. And according to Mark’s account the women end up fleeing the tomb “because they were afraid.” Mark leaves this completely unresolved. Very Kafkaesque.

The spirit/muse/guides sent me to reflect on Sartre’s Nausea. I’m more familiar with Sartre’s No Exit, and his other philosophical works like Being and Nothingness, but when my son introduced me to Nausea several years ago, I couldn’t find my way through to the end. (One of my retirement goals is to lock myself in my library and not come out until I have finished reading this ghastly impactful work.) Sartre experienced the death of his father before he was two. In his teenage years Sartre’s mother remarried and he intentionally abandoned his relationship with his mother because of it. Trauma. Loss. Pain.

The reason I share these fragmented thoughts with you is because I am convinced that the trauma of loss is the one thing we share in common as human beings. “Healing” is overrated. Some traumas never heal. They season. They make us wiser. So, I would urge, in the power we all wield through our individual abilities to use language, to be careful not to make the overly simplistic binary connection between trauma and healing too quickly, as if it is a given. Platitudes of healing, especially the religious kind, are repulsive. They pour salt on the wound. I know this sadly from experience. And to this I must insist, some traumas never heal.

Both Kafka and Sartre, and many others we are all aware of, Nietzsche comes to mind, are honest about what I call the primal retch, the moment when the trauma is exposed, imposed on us like an unwanted, intentionally avoided load, a weight so horrible to contemplate that we wrap ourselves in petty euphemisms to convince ourselves that it could never happen. And then, all of a sudden, it does. Primal retch is the immediate, burning failure of words to make sense of what’s happened. Then the long and painful path of seasoning, of gaining wisdom, of (l)earning language that shapes the story of the experience that the retch could only point to, hearts full of grace for each other, learning wisdom that comes from the struggle of abandoning what we once thought of our (infantile) relationship with God, and embracing the dark mystery of what we don’t yet know, of what we never really knew, but now feel compelled to embrace. The seasoning, the wisdom, the courage as well as the encouragement, and if we must say it, healing, that comes through telling our stories.